MCQS:Understanding the Nature of the GP Fellowship Multiple Choice Exam

The GP Fellowship multiple choice examination, whether approached through the Applied Knowledge Test or the structured MCQ pathways, represents far more than a test of recollection. It is deliberately constructed to mirror the nuanced reasoning that general practitioners employ in real clinical practice. Candidates often presume that such an exam is inherently simple because the correct answer ostensibly resides on the page. Yet the artifice lies in the subtle layering of possible answers, the delicate manipulation of language, and the demand for alignment with contemporary Australian guidelines and evidence-based best practice. To comprehend its nature, one must first understand how these examinations have evolved into a sophisticated filter of clinical aptitude.

The intricate foundation of the Applied Knowledge Test and clinical multiple choice challenges

The early iterations of medical knowledge testing placed emphasis on rote memorisation. Over time, as healthcare delivery in general practice grew more complex, assessments needed to capture more than a candidate’s ability to recall a drug name or diagnostic criterion. Today, the examiners carefully engineer clinical stems that echo authentic consultations, from the commonplace respiratory infection to intricate presentations of chronic illness or psychosocial complexity. The candidate must interpret these stems with precision, then select not just a plausible answer but the one most correct for the situation at hand. This requirement transforms the multiple choice exam into an intricate test of judgement rather than simple memory.

Reading the stems with meticulous care becomes the keystone of success. The difference between a request for the most likely diagnosis and a request for the most important diagnosis is not trivial. The examiner’s phrasing alters the entire logic of the answer. A student rushing through the paper, perhaps driven by stress or misplaced confidence, may succumb to the lure of a distractor. These distractors are not careless inclusions; they are deliberately plausible, constructed to resemble common errors in clinical reasoning. They may include treatments that are generally used but are not ideal for the particular patient scenario described. They may also feature diagnostic terms that look convincing but are subtly inconsistent with the history or examination findings provided in the stem.

This complexity explains why many candidates discover that the exam is more taxing than they initially anticipated. It demands both depth and agility of thought. One cannot rely solely on instinct, as instinct may be clouded by prior habits or anecdotal experiences. Instead, one must anchor decisions in well-honed clinical reasoning shaped by the latest evidence. The examiners’ reliance on Australian practice guidelines underscores this point. A doctor who practices in another system, even with years of experience, might stumble if unfamiliar with the local standard. For example, a management plan widely accepted in another country could be deemed inappropriate in the context of Australian guidelines. The exam does not simply evaluate whether a candidate knows medicine; it evaluates whether they know how to practice medicine safely and effectively in the Australian general practice environment.

Equally significant is the cognitive burden imposed by absolutes. When a candidate encounters an option containing words like always, never, impossible, or total, it is worth pausing to consider whether reality truly functions in such rigid terms. Medicine rarely conforms to absolutes, and a single counterexample is sufficient to render an absolute statement incorrect. This intellectual discipline of rejecting absolutes unless incontrovertibly justified is a hallmark of clinical reasoning, and the exam deliberately tests whether candidates can apply it under pressure.

The design of the exam also incorporates subtle traps linked to human psychology. Under duress, people read quickly and often skip key words. A single overlooked modifier such as first-line, most appropriate, or immediate can change the answer entirely. Stress-induced haste can therefore be as dangerous as ignorance. Candidates must cultivate a rhythm of attentive reading, almost like a disciplined mantra: pause, parse, interpret, then answer. This rhythm can prevent careless mistakes that would otherwise cost valuable marks.

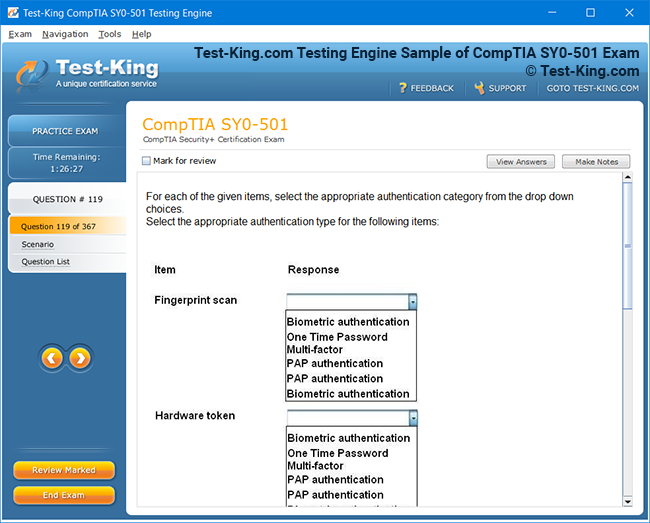

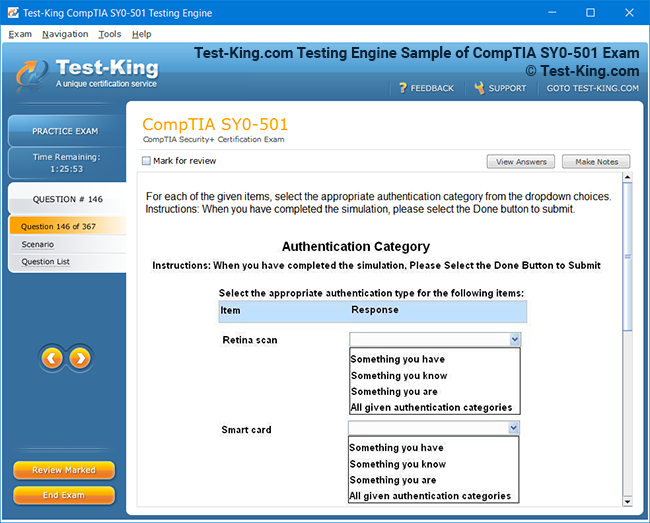

Beyond the wording itself, the exam sometimes demands interpretation of supplementary material such as tables, graphs, or clinical images. Here the danger lies in distraction. A table filled with laboratory values may overwhelm the hurried candidate, tempting them to scan numbers without focus. The wiser approach is to read the question first, clarifying exactly which aspect of the data matters, then hone in on the relevant portion of the table or image. This prevents wasted energy and maintains alignment with the examiner’s intent. In this way, the exam tests not only knowledge but also efficiency in extracting pertinent information from a flood of data, a skill directly transferable to real-life practice.

The heritage of these exams also reflects the collective wisdom of experienced general practitioners. The questions are crafted by those who actively see patients, who understand the subtleties of presentations that appear innocuous but hide grave pathology, and who appreciate how treatment choices are shaped by safety, cost, and practicality in the Australian setting. As a result, the exam draws heavily on cases that walk through the door of everyday clinics. The cough that seems benign, the abdominal pain that masks something sinister, the child with fever whose trajectory could shift dramatically within hours—all these appear within the stems to test whether a candidate can distinguish between the mundane and the critical.

Because of this, preparation cannot be confined to textbooks alone. Every patient seen in the consulting room becomes a potential rehearsal for the exam. The conscientious candidate will review each encounter against current guidelines, ensuring that their management remains aligned with best practice. In doing so, they convert routine work into ongoing preparation. This strategy is not just about passing an exam; it embodies the very ethos of lifelong learning that underpins the vocation of general practice.

One of the most underestimated aspects of the exam is the interplay between time pressure and cognitive load. With hundreds of questions to answer in a finite period, pacing becomes as crucial as knowledge itself. The examiners intentionally calibrate the exam so that candidates must maintain momentum without rushing into reckless answers. This delicate balance tests whether candidates can sustain concentration over several hours, a demand that mirrors the realities of a long day in clinical practice where decisions must be made consistently and safely. The ability to manage time across questions, knowing when to linger and when to move on, often separates those who pass comfortably from those who fall just short.

It is also important to appreciate that the multiple choice format, contrary to popular belief, is not inherently easier than written assessments. In some respects it is more challenging, because the candidate is constantly aware that the correct answer is within reach yet tantalisingly camouflaged. The examiners exploit this psychology, crafting options that each contain a kernel of truth but only one that represents the most correct choice. This forces the candidate to exercise discernment, an intellectual muscle that can only be strengthened through deliberate practice and critical reflection.

When considering why so many capable doctors find this exam difficult, one must look to the underlying cognitive demands. Memory, reasoning, attention, and stress management all converge in the space of a few seconds as the candidate reads a question and decides on an answer. A lapse in any of these domains—whether forgetting a guideline, misreading a phrase, or succumbing to stress—can result in an error. Success requires an integration of knowledge, discipline, and resilience. It is this integration that the exam ultimately seeks to measure.

The GP Fellowship multiple choice exam is thus best understood not as a hurdle of trivia but as a carefully orchestrated challenge designed to reflect real-world medical reasoning. It is a mirror held up to the candidate’s clinical mind, testing not only what they know but how they think, how they interpret, and how they decide. Its sophistication lies in its simplicity: a question, a handful of options, and the demand to choose the single best path forward. Those who prepare with depth, humility, and vigilance discover that this exam, while formidable, is also a fair assessment of their readiness to serve as a safe and competent general practitioner in the Australian landscape.

The essential pathways of learning and applied reasoning for the GP Fellowship multiple choice exam

The preparation for the GP Fellowship multiple choice exam, whether in the form of the Applied Knowledge Test or the traditional MCQ assessment, demands far more than isolated bursts of study. It requires a deliberate cultivation of habits that transform daily practice, intellectual resources, and memory into a finely tuned capacity for clinical reasoning. The perception that one can approach this type of examination with last-minute cramming or superficial review is quickly dispelled once the candidate confronts the rigour of the questions. Success is founded on immersion, repetition, and the capacity to apply theoretical understanding to nuanced patient encounters, a process that must be sustained over months rather than weeks.

A cardinal principle in preparation lies in the transformation of ordinary clinical encounters into reservoirs of study material. Every patient presenting with a rash, a chronic cough, a mood disturbance, or a subtle symptom of fatigue can become a living case study. When candidates discipline themselves to review each encounter against current Australian guidelines, the very act of consulting becomes a rehearsal for the exam. This is not merely a pragmatic approach but a deeply educational one, because it bridges the artificial boundary between theory and practice. By weaving guideline-based management into daily routines, candidates are reinforcing the exact skills and frameworks that examiners seek to test.

The notion of practice is often misunderstood as mere repetition, but in reality it is the conscious structuring of rehearsal to mirror the conditions of the exam. For example, the candidate should work through full-length practice papers released by the RACGP, because these questions are drawn from authentic past assessments. By doing so under timed conditions, the learner begins to internalise the pacing that is crucial on exam day. Many underestimate the cognitive exhaustion that builds when hundreds of questions must be answered in a single sitting. To mitigate this, practice must be more than an occasional activity; it must become a habitual discipline, much like physical training for an athlete.

The value of commercially prepared resources such as Dr MCQ also cannot be overstated. These repositories of questions, designed to replicate the difficulty and nuance of real exams, provide breadth and depth. A candidate might, for instance, select a curated quiz focusing on dermatological presentations one week, then shift to cardiovascular problems the next. By rotating through topics in this systematic manner, gaps in knowledge become visible. Moreover, the process of reflecting on errors, rather than merely celebrating correct answers, is where genuine learning occurs. An incorrect response should not discourage but rather illuminate the contours of misunderstanding that can then be corrected through guideline review and further study.

Peer learning is another invaluable yet often underutilised resource. Forming a study partnership or a small group allows candidates to craft questions for one another, which mirrors the logic used by examiners when creating distractors. The very act of writing a question forces the author to think deeply about what makes an option correct, what makes another plausible but not ideal, and how a stem can be crafted to test subtle aspects of reasoning. Such collaborative engagement cultivates analytical sharpness while simultaneously providing moral support, which can be especially vital during the long and often solitary months of preparation.

The interplay between rote memorisation and applied understanding must also be addressed. While a certain degree of memorisation is unavoidable in medicine—drug dosages, immunisation schedules, diagnostic criteria—the examiners are not primarily testing for the mechanical recall of facts. Instead, they are probing whether the candidate can apply knowledge judiciously in clinical contexts. For instance, it is one thing to know the diagnostic criteria for depression, and another to apply those criteria to a patient presenting with overlapping symptoms of fatigue, insomnia, and chronic illness. Thus, candidates must discipline themselves to study not in isolation but in context, constantly asking how a fact would apply in a real consultation.

Australian practice guidelines form the bedrock of preparation. These guidelines embody the distillation of evidence into practical recommendations, and the examiners rely upon them when framing the correct answer. A candidate may be well versed in international literature, but if their response diverges from Australian standards of care, they will lose marks. This makes it imperative to consult resources such as national therapeutic guidelines, RACGP publications, and current clinical frameworks. Embedding these into daily practice not only equips the candidate for the exam but also strengthens the safety and quality of care delivered to patients.

Another cornerstone of preparation is the ability to manage and measure time effectively. Candidates should calculate how many minutes are available per question and rehearse this rhythm repeatedly. During practice sessions, it is valuable to keep a clock in plain view and to develop the discipline of moving on from difficult questions rather than lingering too long. Those who fail often describe a sense of running out of time and being forced into a hasty scramble at the end. Such an outcome can be prevented by diligent rehearsal, where the candidate simulates exam conditions again and again until the rhythm becomes second nature.

The art of intelligent guessing is equally relevant in preparation. Candidates must become adept at discarding clearly incorrect options, recognising that in an exam without negative marking, there is no penalty for attempting every question. Practicing this skill can be surprisingly powerful, as it trains the mind to operate under conditions of uncertainty. It also reinforces the principle that an imprecise answer, such as a vague diagnosis, is often less correct than a precise one. By rehearsing this discernment repeatedly, the candidate strengthens their ability to eliminate distractors and converge on the correct choice under pressure.

Stress itself becomes a hidden curriculum in preparation. The anxiety of the exam hall cannot be wished away, but it can be rehearsed against. Simulated exam conditions, where candidates subject themselves to full-length timed tests, cultivate familiarity with the discomfort. Over time, the unfamiliar transforms into something routine, and the candidate’s body learns not to panic when the pressure builds. This type of stress inoculation is vital, because unchecked nerves can lead to errors in reading, interpretation, and pacing. By learning to operate in a state of controlled tension, the candidate ensures that the real exam does not overwhelm them.

A subtle yet important aspect of preparation is the cultivation of language awareness. The examiners are meticulous in their phrasing, and candidates must attune themselves to these linguistic cues. Words like immediate, first-line, and most appropriate are not interchangeable; they signal different priorities and different correct answers. Developing an ear for these distinctions requires conscious attention. One strategy is to practise reading questions aloud, listening for the rhythm and emphasis of the phrasing. In doing so, the candidate begins to hear the nuances that might otherwise be skimmed over in silent reading.

Preparation also demands a deep appreciation of the interplay between knowledge and reasoning. The candidate is not merely a vessel of facts but an interpreter of contexts. For example, knowing that antibiotics are not indicated for viral infections is a baseline fact. But when confronted with a stem describing a patient with high fever, chest pain, and focal lung findings, the candidate must integrate this fact with clinical reasoning to arrive at the most correct answer. Thus, the exam measures synthesis rather than storage, and preparation must mirror this synthesis at every opportunity.

In practice, the most successful candidates treat preparation as a continuous immersion rather than a discrete task. They interlace study with daily work, converting ordinary consultations into exercises in applied knowledge. They review guidelines not sporadically but regularly, making them living documents in their clinical repertoire. They practise under timed conditions until pacing becomes instinctive. They collaborate with peers, both to sharpen their own reasoning and to broaden their exposure to diverse perspectives. They cultivate resilience in the face of stress and develop linguistic sensitivity to the subtleties of exam phrasing.

Preparation for the GP Fellowship multiple choice exam is therefore a journey of integration. It integrates daily practice with structured rehearsal, guidelines with reasoning, memorisation with application, and stress with discipline. It is not about the accumulation of facts alone but about the transformation of knowledge into clinical wisdom under the constraints of time, pressure, and exacting standards. In this way, preparation becomes both an intellectual discipline and a professional rite of passage, shaping not only exam success but the very manner in which one approaches the vocation of general practice.

The art of pacing, reasoning, and precision for the GP Fellowship multiple choice assessment

The day of the GP Fellowship multiple choice exam, whether in the form of the Applied Knowledge Test or the structured MCQ, often arrives with an air of trepidation. Months of preparation, endless hours of practice, and the careful assimilation of guidelines culminate in a single session where pacing, clarity of reasoning, and attention to detail determine the outcome. This is not a test where success rests on knowledge alone; it is equally a challenge of stamina, discipline, and strategic execution. Understanding how to navigate this landscape of questions with composure is essential for every candidate, and the principles of exam-day tactics require careful cultivation long before the paper is placed in front of you.

Pacing stands at the core of the experience. Each candidate is confronted with a finite number of questions, and each question demands thought, yet time is relentlessly limited. The arithmetic of the exam is unforgiving: divide the total time by the number of questions, and the margin for indulgence becomes clear. Spending twice as long on a tricky scenario means sacrificing the opportunity to approach the next one with adequate focus. This delicate equilibrium requires rehearsal during preparation, so that by the time the actual exam begins, a natural cadence has already been internalised. Candidates must learn to feel the passage of time almost instinctively, knowing when to linger for precision and when to move forward with decisive efficiency.

Flagging questions becomes an indispensable tactic in this context. No matter how well-prepared a candidate is, there will inevitably be questions that provoke doubt, uncertainty, or outright confusion. To dwell upon them at length is to invite a collapse in pacing. Instead, the prudent approach is to mark them for later review, move ahead with confidence on those that can be answered readily, and return to the flagged items once the easier ground has been covered. This tactic ensures that the exam is not derailed by one difficult question, but instead progresses steadily toward completion.

The practice of completing easier questions first is more than a matter of efficiency; it also stabilises the psyche. Early success builds momentum, quiets anxiety, and bolsters confidence. Each correctly answered question affirms that the months of preparation were worthwhile, and this affirmation provides a psychological shield against the creeping doubt that can sabotage performance. By contrast, beginning with difficult questions can induce panic, which then erodes the quality of reasoning for the remainder of the exam. Thus, prioritisation of simpler tasks is as much about mental resilience as it is about time management.

Intelligent elimination is another keystone of effective exam strategy. Rarely will a candidate encounter a question where the correct answer is immediately obvious without consideration. More commonly, several options appear plausible. In such cases, the mind must work by exclusion, methodically discarding those that are inconsistent with the stem, incompatible with guidelines, or expressed in absolute terms that defy clinical reality. Each eliminated option reduces the field, and with it, the burden of choice. This process mirrors the diagnostic reasoning employed in practice: just as a clinician rules out improbable conditions to narrow a differential, so must the candidate rule out improbable answers to reach the most correct conclusion.

Absolutes pose a particular danger. An option that insists a condition is always present, that a treatment is never appropriate, or that a circumstance is entirely impossible is rarely correct. Medicine resists such rigidity. The discerning candidate will recognise that exceptions almost always exist, and a single counterexample undermines the validity of such definitive statements. Eliminating absolutes early can save precious time and reduce cognitive clutter.

Stress management in the heat of the exam hall requires deliberate strategies. Anxiety often manifests in rushed reading, skipped words, or misinterpretation of stems. Yet the very design of the exam hinges on careful reading. Subtle modifiers such as immediate, most appropriate, or first-line shift the meaning of a question entirely. To combat the corrosive effect of stress, candidates must cultivate a ritual of deliberate reading. Some find it useful to whisper the stem quietly under their breath, while others underline or mentally highlight key terms. The important principle is that reading should not be passive but active, engaging both attention and memory to ensure comprehension before an answer is attempted.

Questions incorporating tables, graphs, or images add another layer of complexity. The temptation is to scan the data first, only to become entangled in extraneous details. The wiser approach is to read the question before turning to the supplementary material. This clarifies what aspect of the data is relevant, preventing unnecessary distraction. A graph depicting lung function, for example, may contain a wealth of detail, but if the question pertains only to the interpretation of one curve, the rest is irrelevant. Precision in focus is thus as vital as knowledge itself.

The practice of covering answer options initially can sharpen clarity of thought. By forcing oneself to consider the likely answer before viewing the options, the candidate generates an independent hypothesis. Once the options are revealed, this hypothesis can be compared to them. Often, this technique prevents the candidate from being swayed by distractors that might otherwise appear convincing. It aligns the exam experience with real practice, where a clinician formulates a provisional diagnosis before testing it against investigations or guidelines.

Time discipline extends beyond pacing to encompass review. It is wise to preserve several minutes at the end of the exam for revisiting flagged questions. During this review, candidates should exercise restraint: changing an answer without compelling reason often leads to error. Initial instincts, when grounded in knowledge and careful reasoning, are frequently correct. However, if upon re-examination it becomes clear that a misreading or misinterpretation occurred, then a change is justified. This balance between trust in initial judgement and openness to correction epitomises the art of reflective clinical practice.

There will inevitably be questions where knowledge is incomplete, memory falters, or reasoning yields no clear answer. In such moments, candidates must remember that there is no penalty for guessing. Leaving a question unanswered is a wasted opportunity. Intelligent guessing involves discarding obviously incorrect options, favouring specific over vague answers, and avoiding absolutes. Even if certainty is unattainable, narrowing the field enhances the probability of selecting the correct answer. In this sense, the exam rewards not only knowledge but also strategic pragmatism.

One must also be vigilant against the trap of revisiting questions excessively. To linger repeatedly on a single puzzling stem drains both time and emotional stability. The candidate may begin to ruminate, second-guessing earlier decisions and undermining confidence. Better to answer provisionally, flag for later review, and move forward. The discipline to move on, even in uncertainty, reflects the reality of clinical work where decisions must often be made without perfect information.

The psychological atmosphere of the exam hall amplifies every sensation. The sound of pens scratching, the shuffle of papers, the occasional cough—all become magnified by stress. Candidates should anticipate this environment and rehearse techniques to maintain focus. Breathing exercises, brief mental resets, and a steady internal rhythm can preserve equilibrium. The ability to think clearly amidst distraction is itself a skill, one that serves both the exam and the daily practice of medicine where interruptions and pressures abound.

Ultimately, the strategies employed during the GP Fellowship multiple choice exam mirror the qualities of a capable general practitioner: efficiency without haste, attention to detail without obsession, confidence tempered by humility, and the ability to act decisively in the face of uncertainty. The examiners are not only testing what a candidate knows but also how they think, how they manage pressure, and how they navigate the balance between speed and precision. Success lies in harmonising these qualities, transforming knowledge into action with poise and foresight.

Mastering the inner terrain of stress, confidence, and mental clarity during the GP Fellowship multiple choice exam

The GP Fellowship multiple choice exam, whether in the Applied Knowledge Test or the structured MCQ form, is not solely a contest of medical knowledge. It is, in equal measure, a test of psychological resilience, emotional equilibrium, and the capacity to maintain clarity of thought under duress. The pressures of such an exam can be relentless: hours of intense concentration, hundreds of carefully engineered questions, and the awareness that each decision contributes to the final outcome. To navigate this demanding experience, candidates must prepare not only their intellect but also their inner landscape, cultivating strategies that enable calm reasoning amidst the turbulence of stress.

Anxiety is one of the most pervasive challenges faced by candidates. It arises before the exam day, mounts during the reading of instructions, and often crescendos when encountering the first difficult question. This anxiety manifests physiologically through racing heartbeats, sweaty palms, and shallow breathing, but its more insidious effect is cognitive. Anxiety narrows attention, reduces working memory, and increases the tendency to misread or skip crucial words in the stem. The danger is not that knowledge disappears, but that access to knowledge becomes blocked by a storm of nervous energy. For this reason, preparation must include deliberate techniques to manage anxiety. Controlled breathing, rehearsed affirmations, and the habit of pausing to steady oneself before reading a question can transform panic into focus.

Confidence, by contrast, functions as a protective shield. A candidate who has prepared thoroughly, practised under exam conditions, and reflected on their progress is more likely to approach the paper with equanimity. Confidence is not arrogance; it is the quiet assurance that one has done the work required and can trust the process. This assurance tempers the urge to second-guess every decision, which is a common pitfall. The phenomenon of changing correct answers to incorrect ones, driven by wavering self-belief, can devastate performance. Cultivating confidence through repeated rehearsal and constructive feedback is therefore a central pillar of psychological preparation.

Fatigue represents another hidden adversary. The exam is not a sprint but a marathon, requiring sustained concentration over several hours. Mental exhaustion creeps in gradually, eroding precision and encouraging shortcuts. Candidates may find themselves reading stems superficially, skipping over nuanced words, or succumbing to distractors that would have been rejected earlier in the exam. Preparation must therefore include endurance training for the mind. Engaging in full-length practice exams, maintaining steady sleep routines in the weeks prior, and practising sustained reading and reasoning exercises are methods of building this cognitive stamina. Just as athletes train their bodies to endure, candidates must train their minds to remain sharp across the length of the exam.

Adrenaline, though often maligned, can be harnessed as a source of energy. The heightened alertness and sharpened senses that accompany adrenaline can be advantageous if channelled correctly. The key lies in avoiding the tipping point where adrenaline becomes overwhelming and converts into panic. Techniques such as visualisation, where the candidate imagines themselves calmly progressing through the exam hall, can prime the nervous system to respond constructively. Similarly, rituals—such as taking a deep breath before turning each page—anchor the mind and prevent adrenaline from spiralling out of control.

The balance between instinct and clinical reasoning is another psychological dynamic that plays a profound role. Instinct is often informed by years of clinical exposure, allowing doctors to recognise patterns quickly. Yet instinct alone is not always reliable, especially in a high-stakes exam where distractors are designed to exploit superficial recognition. Clinical reasoning, on the other hand, is a slower, deliberate process that weighs evidence and aligns decisions with guidelines. The challenge is to harmonise the two. A well-prepared candidate may experience an immediate instinctive pull toward one answer but must then validate this choice through reasoning. This dual process—swift intuition checked by rational deliberation—ensures accuracy without paralysis.

Overthinking presents its own hazards. Faced with an uncertain question, candidates may ruminate endlessly, imagining unlikely scenarios or doubting every option. This spiralling not only consumes time but also disrupts pacing and diminishes overall performance. To combat overthinking, candidates must practise the art of sufficiency: recognising when enough reasoning has been applied to justify a decision and moving on without regret. Trusting the preparation undertaken, and understanding that perfection is unattainable in such an exam, liberates the candidate from the destructive cycle of endless doubt.

The psychological strain is further intensified by the exam environment itself. Rows of candidates seated in silence, the visible presence of supervisors, and the constant ticking of a clock create an atmosphere heavy with pressure. Some may even find the mere act of signing in and waiting for the paper to be distributed an ordeal in itself. Acclimatisation to this environment can be rehearsed by taking practice exams in public libraries or noisy cafés, training oneself to focus despite distractions. By rehearsing under less-than-ideal circumstances, the candidate develops resilience that will serve them well in the sterile quiet of the exam hall.

Mental clarity depends not only on exam-day strategies but also on habits established in the weeks leading up to the exam. Sleep hygiene is paramount, as even small deficits in rest can impair memory, concentration, and emotional stability. Nutrition plays a subtler role, with steady energy derived from balanced meals proving more effective than last-minute reliance on caffeine or sugar. Exercise, too, contributes by regulating stress hormones and enhancing cognitive performance. These lifestyle factors may appear peripheral to academic study, but they form the bedrock of psychological stability when the stakes are highest.

One must also address the phenomenon of anticipatory stress, which often peaks in the final days before the exam. Candidates may find themselves catastrophising, imagining failure despite months of diligent preparation. This anticipatory stress can erode confidence and lead to last-minute cramming that disrupts sleep and destabilises rhythm. Counteracting this requires perspective: reminding oneself that preparation has been steady, that knowledge has been consolidated, and that the exam is not a trap but a fair assessment of readiness. Some candidates find it helpful to engage in mindfulness practices, where attention is anchored in the present moment rather than in imagined disasters.

Resilience in the face of setbacks during the exam is another psychological necessity. It is inevitable that some questions will confound even the best-prepared candidate. The danger lies not in encountering difficulty but in allowing it to cascade into despair. The resilient candidate acknowledges the difficulty, marks the question for later review, and presses on with equanimity. This capacity to recover swiftly from small failures is a hallmark of psychological strength and often separates those who complete the paper confidently from those who unravel midway.

The final psychological dimension is the cultivation of self-awareness. Every candidate has personal vulnerabilities: some read too quickly, others dwell too long, and still others are prone to panic when encountering unfamiliar content. To identify these tendencies requires honest reflection during practice exams and feedback from mentors or peers. Once identified, these vulnerabilities can be addressed directly. The candidate who reads too quickly can practise slowing down and underlining key words. The one who dwells too long can train themselves to impose time limits on each question. Through this process of self-awareness and adjustment, candidates shape their mental habits into forms that support success.

The GP Fellowship multiple choice exam is, in essence, as much a psychological trial as an academic one. It tests endurance, composure, and the ability to sustain clarity amidst pressure. By rehearsing strategies to manage anxiety, cultivating confidence through preparation, building endurance, harnessing adrenaline, balancing instinct with reasoning, and developing resilience, candidates equip themselves with the inner resources required for success. Just as clinical practice demands not only knowledge but also calm judgement in moments of uncertainty, so too does the exam demand a union of intellect and psychological poise.

Integrating preparation, mindset, and practice for long-term mastery

When preparing for the GP Fellowship multiple choice exam, whether it is the Applied Knowledge Test or the structured MCQ, candidates must bring together not only the accumulation of knowledge but also the refinement of practical strategies, psychological steadiness, and an unyielding sense of purpose. This assessment is not designed to reward superficial memorisation but to evaluate how effectively a doctor can apply medical understanding to real-world clinical scenarios, aligning their decision-making with best practice in Australian general practice. To achieve mastery, the candidate must combine diverse strands of preparation into a cohesive framework that supports consistent performance across the entirety of the exam.

A central principle of readiness is familiarity with the style and structure of the exam. Each question stem is crafted with deliberation, and the language used is precise. Candidates must therefore train themselves to scrutinise every word, resisting the temptation to skim or leap prematurely toward an answer. Many mistakes occur not because the knowledge is absent but because the wording has been misunderstood. Distinctions such as “most appropriate next step,” “most likely diagnosis,” or “most important investigation” are critical. Misinterpreting these subtle cues can divert even a well-prepared candidate toward distractors that appear plausible. To counteract this, reading deliberately, underlining key words mentally or visually, and pausing before committing to an answer is invaluable.

Time management, though often discussed, cannot be overstated. A test of this scale requires candidates to maintain a steady rhythm, neither rushing in panic nor lingering excessively on difficult items. A practical approach is to calculate in advance how many minutes can be devoted to each question, while still reserving a buffer for reviewing at the end. Candidates who practise this discipline during mock exams train their minds to respect the pace required. If a perplexing question emerges, it is prudent to mark it and return later, rather than sacrificing subsequent marks. The art of pacing is less about speed than about balance: ensuring each question receives sufficient but not excessive attention.

Practice with authentic materials remains one of the strongest predictors of success. The practice AKT provided by the RACGP offers an indispensable opportunity to encounter the exact style of questioning and to rehearse under conditions that simulate the pressure of exam day. Supplementing this with curated question banks, such as those developed through professional services, ensures repeated exposure to diverse clinical topics. Beyond purchased materials, candidates may enrich their study by collaborating with peers to devise their own clinical scenarios and questions. This not only strengthens understanding but also builds adaptability, as unpredictable questions demand flexible reasoning.

Clinical practice itself should be viewed as a living classroom. The patients encountered daily embody the range of presentations that form the foundation of the exam. By deliberately pausing after consultations to revisit guidelines, review diagnostic frameworks, and examine treatment recommendations, the candidate transforms routine work into active preparation. This habit deepens the connection between theoretical learning and practical decision-making, an alignment that the exam is explicitly designed to test.

One often overlooked resource is the public exam report released after each cycle. These reports highlight common pitfalls, provide illustrative examples, and offer examiners’ reflections on candidate performance. By studying them closely, a candidate can glean insights into recurring patterns of error and avoid repeating the same mistakes. The wisdom contained in these documents is distilled from thousands of scripts and represents a rare glimpse into the expectations of the examiners themselves.

The psychological dimensions of performance must also be integrated into preparation. Stress management is not peripheral but central. A candidate who succumbs to anxiety, panic, or doubt risks undermining months of diligent study. Techniques such as mindfulness, visualisation, controlled breathing, and positive affirmations are not indulgences but essential skills for sustaining equilibrium. Confidence should be built through repetition and reflection, while humility ensures that overconfidence does not blind the candidate to traps. Resilience allows one to recover swiftly from difficult questions, maintaining composure and momentum throughout the paper.

Nutrition, sleep, and physical activity contribute more than is often acknowledged. A rested mind processes information more efficiently, and a well-fuelled body sustains concentration. Neglecting these elements, particularly in the final days before the exam, can sabotage months of work. Establishing a rhythm of steady rest, balanced meals, and moderate exercise supports not only intellectual clarity but also emotional steadiness.

During the exam itself, candidates must remember that every question carries equal value. It is unwise to devote disproportionate energy to a single complex problem while leaving easier questions unanswered. Beginning with questions that feel more accessible can build momentum, reduce nervousness, and secure marks before fatigue sets in. This approach also frees mental space for later revisiting the more challenging items with greater confidence.

Answer selection requires a blend of reasoning and discernment. Distractors often appear plausible because they are partially correct, overly broad, or subtly misaligned with the question stem. To unmask them, candidates should test each option against the stem, discarding those that contradict clinical guidelines or introduce unnecessary absolutes. Words such as always, never, or impossible often signal flawed options, as clinical medicine rarely allows for absolutes. In contrast, specific answers that match the nuance of the clinical presentation tend to hold greater validity.

Graphical data, tables, or images should be approached systematically. Reading the question first provides direction, guiding the eye toward relevant aspects of the visual material. Without this orientation, candidates may become lost in extraneous details, wasting precious time.

Ultimately, success is built not only upon what is known but upon how knowledge is applied under pressure. The GP Fellowship multiple choice exam is less an abstract test of facts than a practical assessment of clinical reasoning. By preparing diligently, reading carefully, pacing wisely, practising authentically, reflecting on feedback, managing stress, and sustaining clarity, candidates place themselves in the strongest position to demonstrate competence.

Conclusion

Mastering the GP Fellowship multiple choice exam is not the product of last-minute cramming or blind luck but the culmination of months of disciplined preparation, balanced with psychological steadiness and practical strategies. It demands integration: the weaving together of knowledge, reasoning, pacing, resilience, and composure. Each candidate must prepare not only intellectually but also emotionally and physically, ensuring that the conditions of exam day mirror those rehearsed in practice. By respecting the nuances of wording, maintaining steady pacing, learning from authentic materials, and harnessing the lessons of daily clinical practice, the candidate transforms anxiety into readiness and uncertainty into confidence. In the end, this exam is not a barrier but a bridge, affirming that the doctor has the capacity to provide care aligned with best practice. Those who approach it with clarity, endurance, and a methodical spirit will not merely survive the experience but emerge with renewed assurance in their professional journey.