Certification: Uniform Securities State Law

Certification Full Name: Uniform Securities State Law

Certification Provider: FINRA

Exam Code: Series 63

Exam Name: Uniform Securities State Law Examination

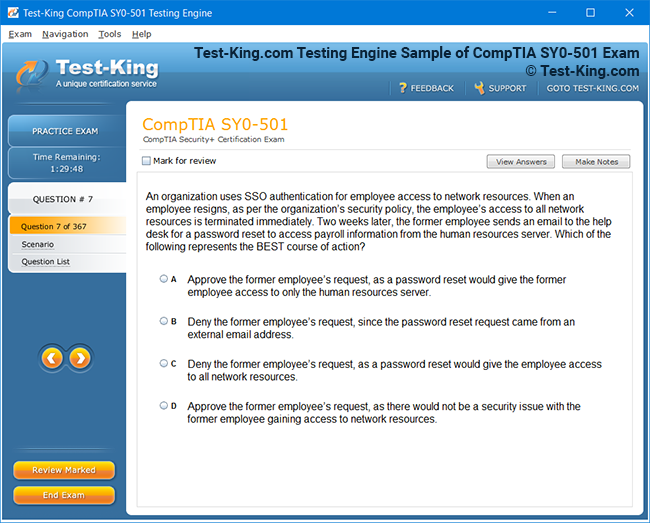

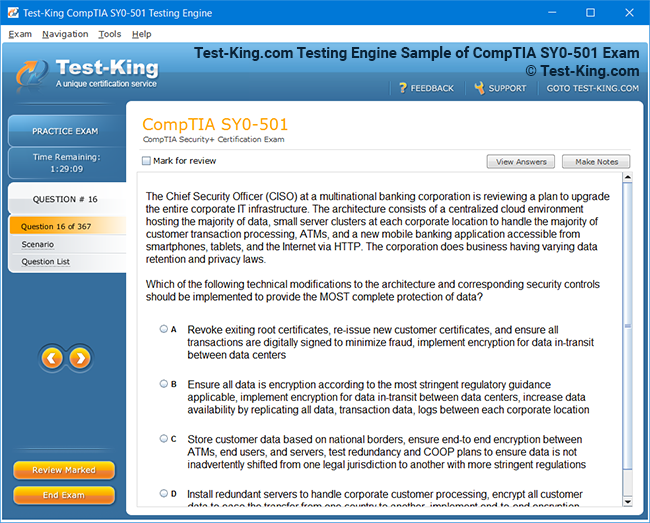

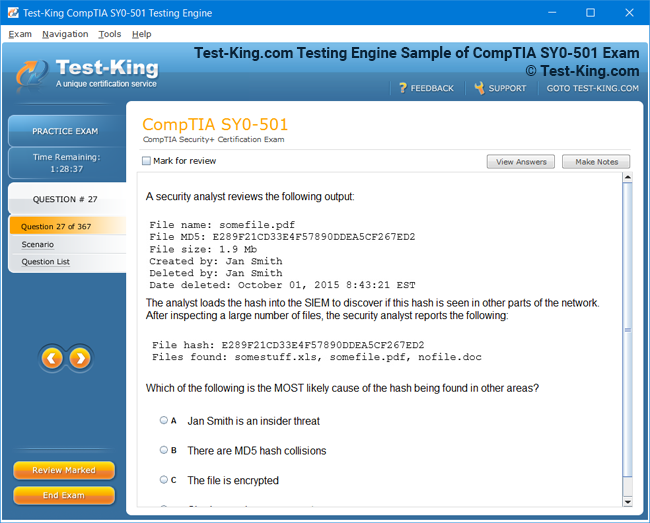

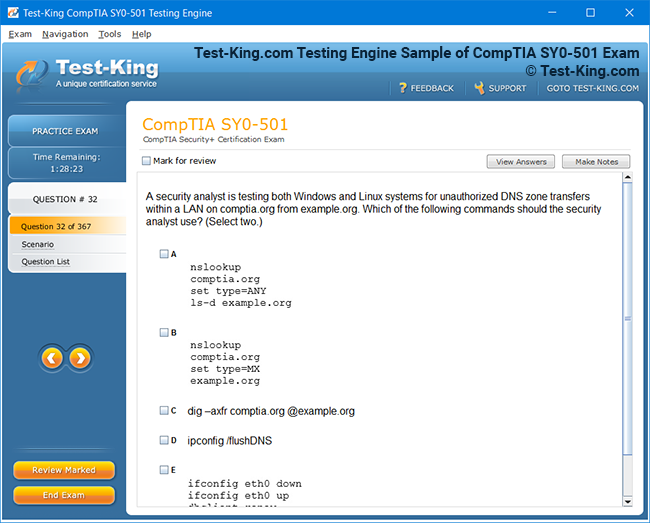

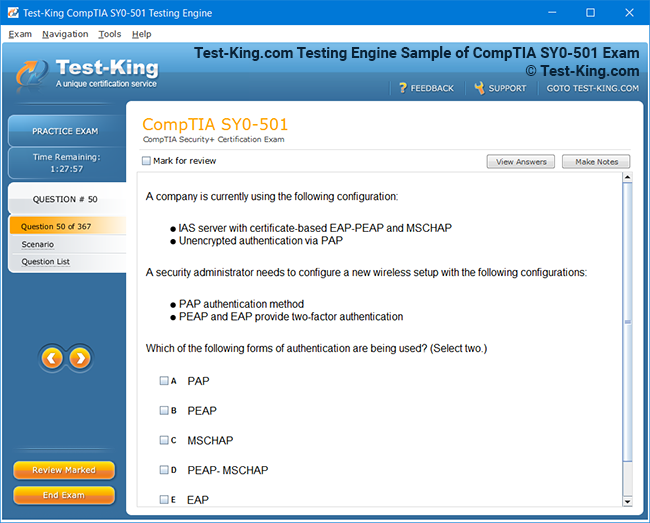

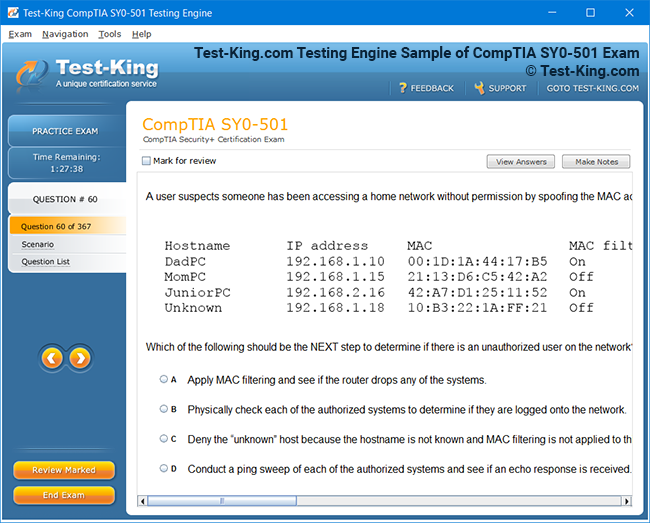

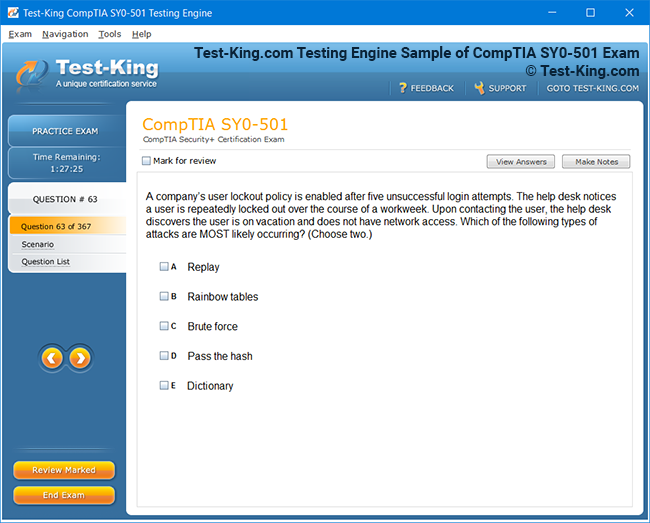

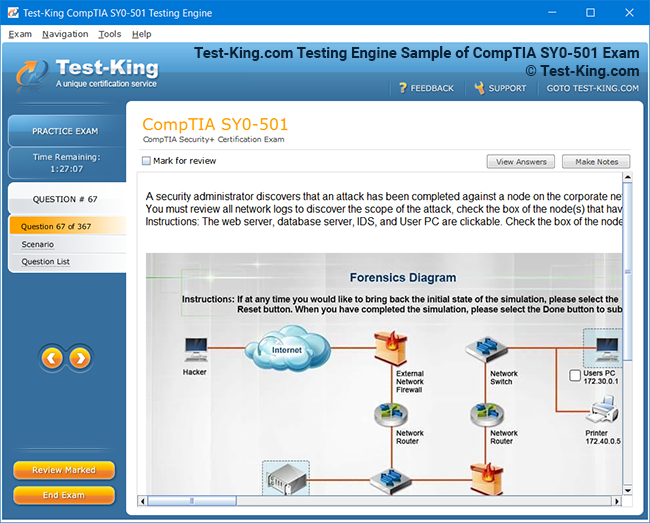

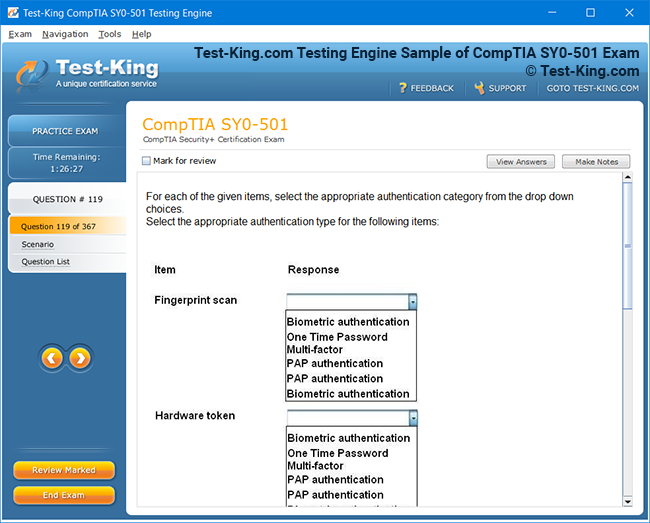

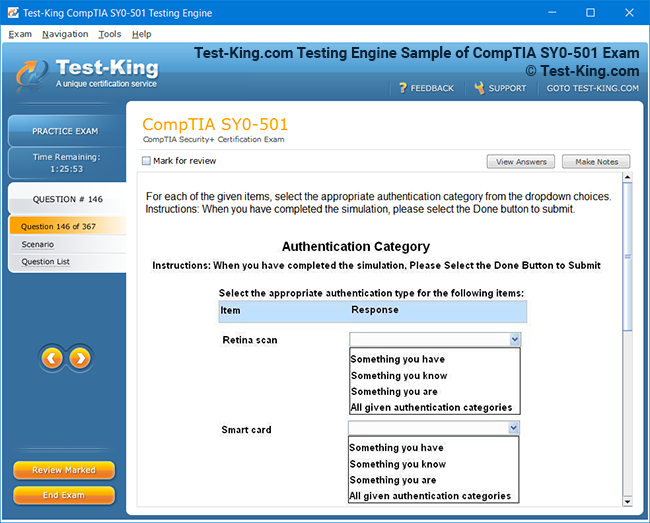

Product Screenshots

Understanding the Series 63 – Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination

The Series 63 – Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination represents a pivotal gateway for individuals aspiring to engage in the sale and distribution of securities across state jurisdictions within the United States. Designed under the guidance of the North American Securities Administrators Association, this examination establishes a unified standard for competence and ethical understanding among securities professionals. Every registered representative who wishes to transact business within a state’s borders must demonstrate mastery of the legal, regulatory, and ethical principles embedded within this assessment. Beyond a mere licensing requirement, the Series 63 examination encapsulates the essence of investor protection, market integrity, and professional accountability, serving as a cornerstone of the broader financial regulatory architecture.

The Foundation of State Securities Regulation and the Path to Professional Mastery

The examination’s structure reflects a thoughtful balance between theoretical knowledge and applied judgment. Comprising sixty-five multiple-choice questions, the test must be completed within seventy-five minutes, demanding not only comprehension but also agility in navigating nuanced regulatory scenarios. Its composition draws from eight distinct yet interconnected topics, each exploring a vital dimension of the securities landscape. These topics include the regulation of investment advisers, adviser representatives, broker-dealers, and their agents; the regulation of securities and issuers; remedies and administrative provisions; communication with customers and prospects; and the ethical practices and obligations expected of professionals in this field. Each thematic sphere mirrors the complexity of real-world securities work, weaving together legislative mandates, administrative protocols, and the subtleties of human interaction in financial transactions.

The first topic in the examination, the regulation of investment advisers, forms the groundwork of understanding how advisory practices are defined and supervised under both state and federal frameworks. Candidates must internalize the meaning of an investment adviser—an individual or entity that, for compensation, engages in providing advice about securities. This portion of the examination evaluates how advisers are registered, the criteria determining state versus federal registration, and the ongoing responsibilities that accompany this status. The notion of fiduciary responsibility emerges as a recurring motif, compelling advisers to act in the best interests of their clients, disclose conflicts of interest, and maintain transparency in every recommendation or transaction.

Parallel to this is the regulation of investment adviser representatives, a topic that underscores the human element within advisory enterprises. Adviser representatives serve as the direct link between the advisory firm and the client, translating institutional expertise into personalized financial strategies. Their registration and oversight are governed by principles similar to those of their employers, yet nuanced by their personal roles and conduct. The examination tests candidates’ comprehension of what constitutes an adviser representative, including those who solicit, provide advice, or manage client accounts. Moreover, it explores the consequences of misrepresentation, the importance of suitability analysis, and the ethical dimension of communication when interacting with clients whose financial wellbeing hinges on professional integrity.

The regulation of broker-dealers stands as one of the most comprehensive portions of the examination, encompassing a vast network of supervision, compliance, and operational standards. A broker-dealer operates as both an intermediary and a principal in securities transactions, executing trades on behalf of clients or for its own account. Understanding the intricate relationship between broker-dealers and the state regulatory authorities is essential, as registration requirements, supervisory obligations, and recordkeeping mandates define the credibility of the entire marketplace. Questions in this domain often challenge candidates to discern the difference between permissible and prohibited conduct, emphasizing the significance of maintaining transparent communication, ensuring fair dealing, and adhering to both the letter and spirit of securities law.

Closely aligned with this is the regulation of agents of broker-dealers. This topic delves into the professional identity of those who act under the supervision of broker-dealers, highlighting their registration procedures, responsibilities, and the potential pitfalls that accompany the role. Agents are required to register not only with their employing firm but also with each state in which they intend to transact business. The examination assesses comprehension of these multilayered obligations and the ethical responsibilities agents bear when soliciting sales, executing orders, or managing accounts. Central to this topic is the notion of post-registration conduct—how an agent must uphold standards of professionalism, maintain records, and avoid conflicts of interest while representing the brokerage’s clients.

The study of securities and issuers introduces candidates to the underlying instruments that define the capital markets themselves. This portion of the examination explores what constitutes a security under the Uniform Securities Act, distinguishing between traditional instruments such as stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, and more complex derivatives or investment contracts. An issuer, in turn, represents the entity that offers or distributes these securities to the public. The candidate’s task lies in understanding the registration processes governing both securities and issuers, as well as recognizing the exemptions that may apply to certain offerings. These exemptions—whether related to private placements, intrastate offerings, or limited transactions—form the backbone of the state’s flexible yet protective approach to capital formation.

A particularly critical aspect examined within this area concerns the exemption for restricted and controlled securities. In practical terms, these exemptions are codified within the Uniform Securities Act and related federal regulations, providing relief from registration for securities that meet specific conditions regarding their distribution and ownership. Understanding this exemption requires more than rote memorization; it demands a grasp of the rationale behind such regulations—the balance between investor protection and the facilitation of legitimate market activity. In essence, the exemption for restricted and controlled securities resides within the complex interplay of statutory and administrative provisions that govern when securities may be sold without prior registration, often under the supervision of both state administrators and federal bodies like the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The examination’s exploration of remedies and administrative provisions delves into the enforcement mechanisms that sustain the integrity of securities law. Candidates must understand the scope of authority granted to state securities administrators, who possess both investigative and corrective powers. These administrators can issue cease and desist orders, impose penalties, revoke registrations, or mandate restitution where misconduct is proven. The regulatory apparatus is designed to function both as a deterrent and as a remedial force, ensuring that malfeasance within the securities industry is met with appropriate consequence. The candidate’s ability to distinguish between administrative, civil, and criminal remedies reflects not only theoretical understanding but also the capacity to navigate real-world compliance scenarios with discernment and foresight.

Communication with customers and prospects forms another central component of the examination, reflecting the recognition that ethical interaction lies at the heart of all securities transactions. This topic emphasizes the necessity of transparent, accurate, and complete disclosure in every form of communication, whether verbal, written, or electronic. Candidates must comprehend the rules governing advertising, correspondence, and sales presentations, as well as the restrictions imposed on testimonials, hypothetical projections, and misleading claims. Furthermore, the exam explores the responsibilities that arise from the formation of customer relationships—how disclosures must be made regarding fees, risks, and potential conflicts, and how records of communications are to be maintained for accountability.

The culmination of the Series 63 examination lies in the study of ethical practices and obligations, which constitutes the largest portion of the test’s weighting. Here, the principles of integrity, honesty, and client-first conduct transcend legal obligation, becoming the moral foundation of the profession. The examination probes candidates’ understanding of ethical behavior as it pertains to compensation structures, fee disclosures, and the treatment of customer funds. It also examines the duties surrounding online data security and the proper handling of confidential information in an increasingly digitalized industry. Questions may address the fine line between persuasion and deception, testing whether a candidate can recognize and avoid actions that could be deemed manipulative or unlawful.

Ethical conduct extends beyond the avoidance of wrongdoing—it involves proactive commitment to the welfare of clients, the maintenance of professional competence, and the cultivation of trust in the marketplace. The candidate who internalizes these ideals not only passes an examination but also inherits a philosophy of service that underpins the financial system itself. The exam, therefore, is not a mere academic exercise but a rite of passage into a vocation that demands intellectual rigor, emotional intelligence, and unwavering ethical fortitude.

Preparing for the Series 63 examination requires a methodical and strategic approach. Candidates benefit from engaging with comprehensive study materials that combine conceptual learning with practice-based reinforcement. Practice tests, for instance, enable candidates to gauge their familiarity with the question structure and the nuanced differences between similar regulatory concepts. Each question serves as an opportunity to refine analytical precision and time management, both essential for success within the seventy-five-minute testing window. On-demand video lessons provide an additional layer of accessibility, allowing learners to revisit challenging concepts, observe real-world applications, and internalize the logical flow of securities regulation.

The integration of artificial intelligence–driven tutoring tools further enriches the learning experience. Interactive platforms can track performance trends, identify areas of weakness, and adapt study recommendations accordingly. This fusion of technology and pedagogy transforms preparation from a solitary endeavor into a guided journey of intellectual discovery. The inclusion of personalized feedback and analytical dashboards provides aspirants with a data-informed perspective on their readiness, transforming abstract preparation into tangible progress.

Beyond the mechanics of study, however, lies the deeper cultivation of a regulatory mindset. To succeed in the Series 63 examination—and, by extension, in the securities profession—one must internalize the ethos of compliance and the psychology of prudence. Every regulation, every disclosure requirement, and every ethical guideline serves a singular purpose: to sustain confidence in the financial system by protecting the investing public from deception, coercion, and negligence. This mindset cannot be memorized; it must be understood and embraced as a living principle guiding every interaction, recommendation, and transaction.

It is worth noting that the structure and difficulty of the examination reflect its dual nature as both a test of knowledge and a measure of professional judgment. While the topics are organized into eight primary domains, their conceptual overlap demands an integrated understanding. For instance, the regulation of broker-dealers is inextricably linked to communication standards and ethical practices, just as administrative provisions intersect with remedies and enforcement. A candidate who studies these topics in isolation risks missing the interconnected logic that binds them—a logic that mirrors the interdependence of real-world financial operations.

The statistical data accompanying the examination underscores its accessibility yet seriousness: over ninety percent of well-prepared candidates pass the test, a testament to the effectiveness of structured study programs and the discipline of dedicated learners. Such success, however, is not achieved through superficial reading or mechanical memorization. It arises from deliberate engagement with the material, repeated exposure to practice questions, and critical reflection upon the ethical dilemmas embedded within the subject matter.

The Series 63 examination stands as a threshold not merely into state-level securities practice but into a broader understanding of the moral economy that underpins all regulated financial activity. Through it, candidates learn that compliance is not an obstacle but a form of stewardship; that regulation is not a restriction but a safeguard for collective prosperity; and that ethics, far from being an abstract ideal, is the functional core of all enduring financial relationships.

As students progress through their study programs, they encounter an evolving dialogue between law, policy, and practice. The regulatory landscape they are entering is dynamic—shaped by economic fluctuations, technological innovations, and shifting social expectations. The capacity to interpret statutes, anticipate regulatory shifts, and respond ethically to unforeseen circumstances becomes as vital as any memorized rule. The examination, in this sense, becomes a microcosm of lifelong professional development, one that rewards curiosity, adaptability, and reflective intelligence.

The journey toward mastering the Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination is both intellectual and moral. It invites candidates to merge precision with empathy, regulation with reason, and knowledge with conscience. Those who approach it not merely as an obstacle but as an initiation into the disciplined art of ethical finance will find within it a profound preparation for the challenges and responsibilities that accompany a career in securities regulation.

In studying the broad canvas of topics—from the definitions of investment advisers to the complexities of ethical obligations—aspirants engage in the reconstruction of their professional identity. They transition from learners of law to custodians of integrity, from interpreters of statutes to advocates of public trust. Each question answered correctly is not only a point toward licensure but also a reaffirmation of a commitment to fairness, transparency, and the enduring value of ethical commerce.

The examination thus symbolizes more than the sum of its topics. It embodies the delicate equilibrium between freedom and oversight, ambition and restraint, profit and principle. It calls upon every candidate to harmonize intellectual acuity with moral discernment, to wield knowledge as both instrument and safeguard. In mastering the intricacies of the Series 63 examination, the aspiring securities agent learns the timeless truth that the greatest strength in finance lies not in speculation or persuasion, but in understanding, responsibility, and unwavering integrity.

Exploring the Foundation of Advisory Oversight and Professional Accountability

The regulation of investment advisers and investment adviser representatives lies at the very heart of the Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination, a cornerstone of financial regulation that safeguards both investors and the integrity of the marketplace. This intricate domain of the Series 63 examination invites candidates to examine the multifaceted relationship between advisers, their clients, and the governing authorities that ensure fair and ethical practices in the financial advisory industry. It is a domain that merges jurisprudence with fiduciary philosophy, calling for a nuanced understanding of both law and conscience.

At its essence, the concept of the investment adviser encompasses any person or entity engaged in the business of providing securities-related advice for compensation. This definition, deceptively simple on its surface, conceals a labyrinth of regulatory nuances that candidates must comprehend in depth. The phrase “engaged in the business” is not merely descriptive—it carries implications regarding the regularity and intent of the adviser’s activities. To qualify under this definition, an adviser must provide personalized or generalized securities advice, derive compensation directly or indirectly for such services, and hold themselves out as being in the business of offering investment guidance. The state and federal frameworks governing this role are harmonized through the Uniform Securities Act and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, each establishing the parameters for who must register, under what conditions, and with which authorities.

Understanding the distinction between state-registered and federally covered advisers is vital for both examination and real-world application. State-registered advisers typically manage smaller portfolios or operate within limited jurisdictions, while federally covered advisers manage assets exceeding the threshold—often one hundred million dollars—and therefore fall under the oversight of the Securities and Exchange Commission. The rationale behind this division lies in efficiency and jurisdictional clarity, ensuring that advisers of significant scale are subject to consistent national oversight while allowing state administrators to supervise smaller, localized practices. This dual structure exemplifies the layered nature of American financial regulation, where federal uniformity and state sovereignty coexist in a delicate equilibrium.

The registration process itself embodies both procedural rigor and ethical declaration. An adviser seeking registration must file the requisite documentation, including the Form ADV, which discloses critical information about ownership structure, disciplinary history, advisory practices, and conflicts of interest. This document functions not merely as a bureaucratic requirement but as a moral covenant—a public assertion of transparency and accountability. The Form ADV also requires advisers to disclose the methods they employ in determining investment recommendations, the sources of their compensation, and the risks associated with their advisory approach. In doing so, it compels advisers to confront the ethical implications of their business models and to present them candidly to potential clients and regulators alike.

Beyond registration, investment advisers are bound by fiduciary duty—a principle that transcends technical compliance and enters the domain of ethical stewardship. The fiduciary standard demands that advisers act in the best interests of their clients, placing client welfare above personal or institutional gain. This obligation manifests in several dimensions: full disclosure of potential conflicts, suitability of recommendations, and the duty of ongoing care in managing client accounts. The fiduciary standard contrasts sharply with the lesser “suitability” standard often applied to broker-dealers, which merely requires that a recommendation be appropriate rather than optimal. Within the fiduciary paradigm, mere adequacy is insufficient; the adviser must pursue the client’s best possible outcome in good faith and with scrupulous honesty.

The Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination evaluates the candidate’s grasp of these principles through a variety of situational questions that test ethical discernment and regulatory comprehension. Candidates must recognize, for example, when an adviser’s actions constitute a breach of fiduciary duty—such as recommending securities that yield higher commissions for the adviser but are not in the client’s best interest. Equally, they must be able to identify when an adviser is inadvertently providing unregistered advice or when a conflict of interest arises from dual compensation structures. These scenarios are designed to assess not only theoretical understanding but also the candidate’s ability to navigate the moral ambiguities inherent in real-world financial practice.

Parallel to the regulation of investment advisers stands the regulation of investment adviser representatives—a category that introduces the human dimension of the advisory process. Adviser representatives are individuals who act on behalf of registered investment advisers, providing advice, soliciting business, or managing client portfolios. Their role is the conduit through which advisory firms interact directly with clients, translating regulatory standards and firm policies into personal financial counsel. The representative is thus both an emissary and a custodian of trust, whose words and actions reflect upon the entire advisory organization.

The regulatory framework governing adviser representatives mirrors that of their employers but carries distinct nuances. Each representative must register not only through their employing adviser but also with each state in which they engage in advisory activities. This dual registration ensures that state regulators maintain oversight of individuals who may directly affect investors within their jurisdictions. Candidates preparing for the examination must understand the specific triggers that require registration, such as providing investment advice, managing client assets, or receiving compensation linked to advisory services. Even individuals performing support roles may fall under regulatory scrutiny if their activities cross into advisory territory.

A critical dimension of regulatory compliance for adviser representatives involves the accurate communication of advisory services. Misrepresentation—whether intentional or negligent—constitutes one of the most common infractions in the industry. Representatives must avoid exaggerating qualifications, performance records, or the benefits of specific investment strategies. Every statement made to a client must be substantiated by verifiable data, and every claim must reflect a balanced view of both risks and rewards. The examination tests candidates’ understanding of such ethical and regulatory requirements through situational analysis, often presenting subtle scenarios that blur the line between persuasion and deception.

Recordkeeping and supervision form additional pillars of adviser and representative regulation. Registered investment advisers are required to maintain detailed records of client communications, recommendations, and transactions for specified durations. These records serve as both a compliance safeguard and an evidentiary resource in the event of disputes or audits. Supervisory systems, in turn, are designed to ensure that representatives adhere to internal controls and external regulations. A failure of supervision—such as neglecting to review communications or trades—can lead to liability for both the individual and the firm. The examination expects candidates to be familiar with the regulatory requirements surrounding these obligations, as well as the administrative consequences of noncompliance.

The fiduciary nature of the adviser-client relationship also extends into compensation practices, a topic of particular regulatory sensitivity. Advisers may be compensated through fees, commissions, or performance-based structures, each carrying unique ethical implications. Fee-only advisers, for example, derive compensation solely from client payments and thus minimize potential conflicts, while commission-based advisers must disclose the inherent incentive to recommend higher-yielding products. Performance-based fees, permissible under specific regulatory conditions, introduce additional complexities by aligning adviser compensation with investment outcomes but also increasing the temptation toward excessive risk-taking. Candidates must be adept at analyzing the regulatory conditions that permit or prohibit such arrangements, as well as the disclosure requirements that accompany them.

Another crucial aspect explored within the Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination concerns the delineation between investment advisers and other financial professionals. The distinction between advisers and broker-dealers, for instance, lies not only in compensation models but also in regulatory philosophy. Whereas broker-dealers operate under transactional relationships governed by suitability standards, investment advisers enter into advisory relationships grounded in fiduciary trust. Similarly, the line between advisers and financial planners may blur, especially when planners provide comprehensive advice that includes securities recommendations. The candidate’s ability to recognize these distinctions reflects an advanced understanding of the financial services ecosystem and the overlapping jurisdictions that regulate it.

In addition to substantive law, the examination emphasizes procedural integrity. Candidates must understand how advisory registration applications are filed, how amendments are submitted when material changes occur, and how disciplinary disclosures are managed. For example, an adviser who undergoes a change in ownership, relocates principal offices, or experiences disciplinary action must promptly update the relevant filings to maintain compliance. Failure to do so may result in administrative sanctions or the suspension of registration. These procedural requirements underscore the dynamic nature of regulatory oversight—compliance is not a static condition but a continuous process of transparency and accountability.

The subject of disciplinary history also introduces a dimension of moral evaluation within the registration process. Advisers and representatives must disclose any past criminal convictions, regulatory infractions, or civil judgments related to the securities industry. This disclosure enables regulators to assess an applicant’s fitness for licensure, balancing the principles of redemption with the necessity of public trust. The examination may test candidates on what constitutes a “statutory disqualification,” including offenses involving fraud, deceit, or the violation of securities laws. In doing so, it reinforces the ethical imperative that those entrusted with the management of public investments must be beyond reproach.

The concept of state authority over advisers and representatives is another area of inquiry that candidates must master. State securities administrators possess the power to investigate complaints, examine records, and enforce disciplinary measures. Their jurisdiction extends over both residents and nonresidents who conduct advisory business within their borders. Administrative actions can include cease-and-desist orders, fines, license revocations, and mandates for restitution. The examination requires candidates to understand the procedural steps of these administrative actions, the due process afforded to respondents, and the rights of appeal.

An understanding of exemptions and exclusions forms an indispensable part of the adviser regulation framework. Certain individuals or entities may be excluded from the definition of investment adviser altogether, such as banks, publishers of bona fide financial publications, and professionals like lawyers or accountants who provide incidental advice. Similarly, exemptions may exist for advisers with limited clientele or those who do not maintain an office within the state. Recognizing these distinctions enables candidates to navigate the gray zones of regulatory application, ensuring that legitimate business activities are not inadvertently subjected to unnecessary oversight.

In parallel, candidates must grasp the concept of notice filing—a mechanism through which federally covered advisers, though primarily regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission, inform state authorities of their presence within the state. This procedural nuance ensures that state administrators retain awareness of advisory activity occurring within their jurisdictions without duplicating federal oversight. Notice filing exemplifies the cooperative federalism inherent in securities regulation, where national uniformity coexists with local vigilance.

The regulation of investment advisers and adviser representatives also encompasses the evolving frontier of digital advisory services. With the rise of algorithmic portfolio management, online advisory platforms, and artificial intelligence–driven recommendations, regulators have expanded their scrutiny to ensure that technological innovation does not compromise investor protection. The examination may present scenarios involving automated advice or hybrid models where human advisers supplement algorithmic recommendations. Candidates must discern when such platforms meet the definition of investment adviser and how their fiduciary responsibilities manifest in a digital context.

Ethical communication remains a unifying thread throughout this domain. Every disclosure, advertisement, and recommendation must convey accuracy, balance, and clarity. Advisers and their representatives must avoid misleading statements, omissions of material facts, or unsubstantiated claims regarding performance. For example, an adviser who promotes a fund’s historical return without disclosing the associated risk profile would violate both ethical and regulatory standards. The examination challenges candidates to recognize such violations and articulate the correct ethical course of action.

The integration of ethical reasoning within regulatory knowledge reflects the broader intent of the Series 63 examination—to cultivate professionals who not only understand the law but embody its spirit. The law provides the boundaries, but ethics provides the compass. Within the context of investment adviser regulation, this means recognizing that compliance extends beyond paperwork and into the daily moral decisions that shape client relationships.

As part of the study process, candidates are encouraged to engage with practice questions that mirror the complexity and subtlety of real-world scenarios. These questions often juxtapose technical compliance issues with ethical dilemmas, compelling candidates to apply both analytical rigor and moral reasoning. For instance, a question might describe a representative recommending a security that yields a higher commission while a lower-cost alternative exists, asking whether this constitutes a breach of fiduciary duty. The correct reasoning requires not only factual knowledge but also an internalized understanding of fairness, honesty, and client-centric judgment.

In mastering the regulation of investment advisers and adviser representatives, aspirants to the securities profession acquire more than a license; they inherit a responsibility to uphold the integrity of the financial ecosystem. Every rule, every disclosure, every prohibition against deceit or omission serves a singular, noble purpose: to ensure that trust—the most fragile and invaluable currency of all—remains intact within the realm of investment and advice. Through this understanding, the Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination transcends its function as an academic test and becomes an instrument of professional formation, shaping not just competent advisers, but ethical stewards of financial truth.

The Structural Pillars of Securities Supervision and Market Integrity

The regulation of broker-dealers and their agents represents one of the most extensive and intricate domains within the Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination. This field encapsulates the entire operational framework through which securities transactions are conducted, managed, and supervised, embodying the mechanisms that sustain both investor confidence and systemic integrity. Broker-dealers are the conduits of the securities marketplace, functioning as intermediaries, facilitators, and often as principals in the exchange of financial instruments. Their agents, in turn, personify the industry’s interface with the investing public, translating institutional mandates into human dialogue, persuasion, and service. The examination of this realm demands an appreciation of not only regulatory statutes but also the ethical substratum that governs trust, duty, and accountability within financial commerce.

The term broker-dealer refers to any individual or entity engaged in the business of buying and selling securities, either for the accounts of others as brokers or for their own account as dealers. This dual identity requires candidates to discern the subtle distinctions between the two capacities. When acting as a broker, the firm executes transactions on behalf of clients and earns commissions or fees for its services. In its capacity as a dealer, the same firm trades for its own benefit, seeking profit through the bid-ask spread or inventory appreciation. The legal and ethical implications of these roles are substantial, as the shift from agency to principal status transforms the nature of the obligation owed to the client. The Series 63 examination probes this understanding through nuanced questions designed to test the candidate’s ability to recognize when each capacity applies and what disclosure or conflict management requirements accompany it.

Registration lies at the core of broker-dealer regulation, serving as the threshold through which legitimacy in the securities business is established. Every broker-dealer must register with the state securities administrator in each jurisdiction where it conducts business, as well as with the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, which serves as the primary self-regulatory organization overseeing the brokerage industry at the national level. Registration is not merely a procedural formality but a vetting mechanism that affirms financial stability, managerial competence, and ethical integrity. The application process typically includes disclosures regarding ownership, control persons, disciplinary history, and financial statements, all of which enable regulators to assess the applicant’s fitness for licensure.

In addition to firm registration, individuals employed by broker-dealers who engage in securities transactions must themselves be registered as agents. This requirement ensures that those who solicit or execute trades possess both the knowledge and the moral disposition necessary to handle investor capital responsibly. The definition of agent within the Uniform Securities Act encompasses any individual representing a broker-dealer in effecting or attempting to effect securities transactions, excluding those whose activities are limited to clerical or ministerial functions. Candidates must recognize that even activities seemingly peripheral to trading—such as soliciting potential clients or transmitting orders—may trigger the need for registration.

The supervisory responsibilities imposed upon broker-dealers form another critical dimension of regulation. Every registered firm is obligated to establish and maintain a supervisory system designed to ensure compliance with securities laws and ethical standards. This system must include written procedures governing all aspects of the firm’s operations, from advertising and sales practices to recordkeeping and trade execution. Designated supervisors or compliance officers are responsible for monitoring the conduct of agents, reviewing transactions, and identifying patterns that might indicate violations or improprieties. The failure to maintain effective supervision can lead to severe administrative sanctions, including suspension or revocation of registration, monetary penalties, and reputational damage that can erode client confidence.

The notion of suitability lies at the ethical center of broker-dealer operations. Agents must ensure that any recommendation or transaction is suitable for the client’s investment objectives, financial situation, and risk tolerance. The suitability obligation requires a thorough understanding of the client’s circumstances, obtained through a process known as the know-your-customer principle. The agent must inquire about income, net worth, investment goals, time horizon, and experience before suggesting any security or strategy. A recommendation that might be suitable for one investor could be wholly inappropriate for another, and regulators emphasize that the burden of proof lies with the agent and the firm. This concept distinguishes the broker-dealer standard of conduct from the fiduciary duty applied to investment advisers, yet both share the underlying premise that client welfare must supersede personal gain.

The regulatory framework also mandates detailed recordkeeping, an essential instrument of transparency and accountability. Broker-dealers must maintain records of customer accounts, correspondence, order tickets, confirmations, and financial statements for prescribed periods, often extending several years. These records serve as both a compliance safeguard and a forensic tool for regulatory investigations. The meticulous maintenance of documentation allows regulators to reconstruct trading histories, verify disclosure compliance, and identify patterns of misconduct such as churning or unauthorized trading. The examination frequently presents hypothetical situations requiring candidates to determine which records must be retained, for how long, and under what circumstances they must be made available to regulatory authorities.

Ethical advertising and communication are integral to broker-dealer regulation. Every communication with the public, whether written, oral, or electronic, must be fair, balanced, and not misleading. This includes promotional materials, website content, email correspondence, and even social media posts. Firms are prohibited from making exaggerated claims, projecting guaranteed returns, or omitting material facts that could mislead investors. Agents are equally accountable for their verbal representations, as even casual remarks made during client interactions can constitute violations if they distort reality or create unjustified expectations. Candidates must understand that regulatory scrutiny extends beyond formal advertisements to encompass all forms of communication, underscoring the pervasive nature of ethical responsibility in the brokerage profession.

The relationship between broker-dealers and agents is governed by both internal contracts and statutory oversight. Agents act as the human extension of their firms, executing orders, soliciting clients, and providing service under the supervision of their employer. However, agents cannot act for more than one broker-dealer at a time unless permitted by specific regulations or dual registration arrangements. The prohibition against dual representation prevents conflicts of interest and ensures loyalty to a single supervisory authority. Additionally, when an agent terminates employment with one firm and joins another, both the old and new broker-dealers must notify the state administrator, ensuring that regulatory records remain current and accurate.

Financial responsibility constitutes a fundamental requirement for broker-dealers. Firms must maintain minimum net capital levels as defined by regulation, designed to ensure their capacity to meet obligations to customers and counterparties. These financial thresholds protect investors from the risks of insolvency or mismanagement. The failure to maintain adequate capital can lead to immediate suspension of operations, reflecting the regulator’s commitment to preempt systemic instability. Furthermore, firms must segregate customer funds and securities from proprietary assets, preventing the misuse or commingling of client property. The examination may challenge candidates to identify situations where such segregation rules are violated, testing their ability to recognize latent risks within brokerage operations.

The state securities administrators wield significant authority over broker-dealers and agents operating within their jurisdictions. Their powers include the ability to conduct examinations, request records, and initiate investigations when misconduct is suspected. Administrative remedies available to these authorities encompass the denial, suspension, or revocation of registration, as well as the imposition of fines or cease-and-desist orders. Candidates must understand the procedural rights afforded to registrants during these actions, including notice, opportunity for hearing, and the right to judicial review. The balance between administrative authority and procedural fairness reflects the regulatory system’s commitment to both accountability and justice.

The concept of unlawful activity underpins many of the examination’s practical scenarios. Broker-dealers and agents are prohibited from engaging in fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative practices. Common examples include misrepresentation of material facts, omission of critical information, front running, insider trading, and unauthorized transactions. Churning—defined as excessive trading in a client’s account primarily to generate commissions—is another frequent topic. The examination expects candidates to distinguish between legitimate trading activity and conduct intended to exploit the client relationship for personal gain. Understanding the nuances of these violations requires both legal knowledge and ethical intuition, as the boundary between zealous representation and abuse of authority is often perilously thin.

The role of broker-dealers in underwriting securities offerings adds another layer of complexity to their regulatory obligations. In this capacity, broker-dealers act as intermediaries between issuers and the investing public, facilitating the distribution of new securities. This process involves additional responsibilities, such as due diligence, disclosure verification, and adherence to offering restrictions. The failure to conduct adequate due diligence can result in liability for material misstatements or omissions within the offering documents. Candidates studying for the Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination must therefore understand the interplay between primary market activities, underwriter obligations, and the antifraud provisions that govern them.

Broker-dealers also play a critical role in secondary market trading, where the ethical dimensions of order handling, price transparency, and best execution come to the forefront. The principle of best execution mandates that broker-dealers seek the most favorable terms reasonably available when executing customer orders. This responsibility encompasses not only price but also speed, likelihood of execution, and overall transaction quality. Agents must avoid directing orders to venues that provide higher remuneration to the firm but disadvantage the client. The examination evaluates a candidate’s ability to recognize such conflicts and to prioritize client interest in the execution process.

In addition to their commercial and regulatory obligations, broker-dealers are entrusted with the duty of safeguarding customer information. The confidentiality of client data—financial statements, account details, investment preferences—constitutes an inviolable trust between firm and investor. Regulations require firms to implement written policies and security measures to protect nonpublic information from unauthorized access or misuse. With the advent of digital trading platforms and electronic recordkeeping, cybersecurity has become a focal point of compliance. A breach not only exposes clients to financial harm but also erodes the foundational confidence upon which the securities industry rests. The examination may incorporate hypothetical scenarios involving data security failures, compelling candidates to apply their understanding of both ethical responsibility and regulatory enforcement.

The concept of continuing education underscores the dynamic nature of broker-dealer regulation. Both firms and their agents are required to engage in ongoing training to remain abreast of regulatory developments, new product offerings, and evolving ethical standards. This lifelong learning process ensures that practitioners remain competent and informed in a marketplace characterized by constant innovation and transformation. The regulators’ emphasis on continuing education reflects their recognition that compliance is not static but an evolving discipline requiring vigilance, introspection, and adaptability.

Ethical dilemmas often arise in areas where legal boundaries are clear but moral considerations remain ambiguous. The solicitation of clients, for instance, presents opportunities for both service and manipulation. Agents must balance persuasive skill with ethical restraint, ensuring that enthusiasm does not devolve into coercion. Similarly, the handling of client complaints demands both procedural propriety and empathetic understanding. An agent who dismisses grievances with indifference risks violating not only professional standards but also the deeper social contract that binds the financial industry to public trust.

The Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination weaves these themes into its assessment of competence, compelling candidates to think as both technicians and moral agents. Through its focus on broker-dealer regulation, the examination illuminates the interconnected web of obligations that sustain the financial marketplace—registration, supervision, suitability, recordkeeping, ethics, and enforcement. The candidate who masters this domain does more than acquire knowledge; they cultivate a disposition of responsibility that resonates far beyond the test itself.

In understanding the regulation of broker-dealers and their agents, one perceives the intricate balance between commerce and conscience, ambition and restraint. Each regulatory requirement, from the registration of an agent to the maintenance of client records, serves as a manifestation of this equilibrium. It is through these mandates that the securities industry achieves both vitality and integrity—a system that rewards enterprise while demanding probity, that permits innovation while enforcing accountability. In this synthesis of law and ethics, the broker-dealer becomes not merely a participant in financial exchange but a guardian of the market’s moral architecture, ensuring that every transaction, however minute, reflects the enduring principles of fairness, transparency, and trust.

Understanding Issuer Obligations, Securities Registration, and Regulatory Exemptions

The regulation of securities and issuers stands as one of the central pillars of the Uniform Securities Agent State Law Examination, embodying the intricate framework through which the investment marketplace maintains order, transparency, and legitimacy. This realm governs the very instruments that form the essence of financial exchange, shaping the ways in which securities are created, distributed, and regulated across various jurisdictions. To understand this field is to grasp the symbiotic relationship between the issuer, the investor, and the regulatory state—a relationship built upon disclosure, accountability, and the prevention of deceit. The examination requires a deep and nuanced comprehension of these interconnected concepts, as they form the bedrock of lawful participation within the securities industry.

A security, in the legal and financial sense, refers to a negotiable instrument that represents either an ownership interest, a creditor relationship, or a right to ownership under certain conditions. These instruments encompass a vast array of products, including stocks, bonds, investment contracts, notes, participation interests, and various derivative structures. The definition is intentionally broad, designed to capture the full scope of investment vehicles that can serve as conduits for capital formation. The Uniform Securities Act defines securities in a manner that focuses not merely on their names but on their economic substance—what they represent and how they function within the broader financial ecosystem. The state securities administrator retains the authority to interpret and classify financial instruments, ensuring that novel or hybrid products do not escape the reach of regulation merely through creative nomenclature.

Issuers, on the other hand, are entities that originate securities for the purpose of raising capital. They may be corporations seeking equity investment, governments issuing debt, or limited partnerships offering participation units. The act of issuance marks the beginning of the life cycle of a security, transforming financial intent into a tangible claim. Every issuer must navigate the regulatory labyrinth governing the registration of securities before offering them to the public. This process, though administratively complex, is essential for maintaining the sanctity of the investment environment by ensuring that all pertinent information regarding the security, its structure, and associated risks is made accessible to potential investors.

The purpose of registration is to promote full and fair disclosure. It does not guarantee the merit of an investment or the solvency of the issuer, but it ensures that investors are equipped with accurate, complete, and non-misleading data upon which to base their decisions. This principle of disclosure over merit is a cornerstone of modern securities law, emphasizing transparency over paternalism. The registration process typically requires the submission of a detailed statement containing information about the issuer’s business operations, financial condition, management, the nature of the securities being offered, and any material risks that might affect investment value. The state securities administrator reviews these documents to verify their completeness and to detect any irregularities or omissions that could mislead investors.

The examination demands familiarity with the three principal methods of securities registration—registration by coordination, registration by qualification, and registration by notice filing. Each of these methods corresponds to different circumstances and issuer profiles. Registration by coordination is most commonly employed when the issuer is simultaneously registering securities with the federal regulator. Under this method, the state registration becomes effective at the same time as the federal registration, provided all requirements have been met. This approach harmonizes state and federal oversight, ensuring consistency across jurisdictions and reducing duplicative administrative burdens. Registration by qualification, conversely, is used when no federal registration exists. It requires a more detailed submission and grants the state administrator greater discretion in determining whether to grant effectiveness. Registration by notice filing is generally reserved for federally covered securities, which enjoy certain preemption from state-level merit review but are still subject to administrative notice and fee requirements.

Exemptions form an equally vital aspect of securities regulation, providing relief from registration under specific conditions. The rationale for exemptions lies in balancing investor protection with market efficiency. Certain transactions or issuances pose minimal risk or involve participants of sufficient sophistication to warrant reduced oversight. Among these exemptions are those granted to isolated non-issuer transactions, which involve secondary sales by investors rather than original offerings by issuers. Similarly, transactions with institutional investors—such as banks, insurance companies, and trust entities—are often exempt, as these parties possess the resources and expertise to evaluate risk independently. The state laws also provide exemptions for limited offerings, where the number of purchasers or total dollar amount of securities sold does not exceed prescribed thresholds.

Another important category includes exempt securities—those that, due to their nature or origin, are considered inherently reliable or subject to alternative regulation. Government securities issued by the United States, its agencies, or municipalities are classic examples, as are securities of foreign governments with diplomatic recognition. Nonprofit organizations, religious institutions, and certain regulated public utilities may also issue securities that qualify for exemption. The Uniform Securities Act emphasizes that even though such securities are exempt from registration, they remain subject to antifraud provisions. Thus, no issuer, regardless of exemption status, may engage in deceit or misrepresentation in the sale of securities.

The antifraud provisions represent the moral and legal core of securities regulation. They prohibit any act, practice, or omission that operates as a fraud or deceit upon investors. This includes false statements of material fact, concealment of significant information, or any scheme intended to manipulate prices or mislead market participants. These provisions are intentionally broad and apply to all persons and transactions involving securities, whether registered, exempt, or private. The state securities administrator holds extensive enforcement authority in this domain, including the ability to investigate suspected violations, subpoena witnesses, examine records, and pursue administrative or civil remedies.

The concept of materiality is essential to understanding antifraud enforcement. A fact is considered material if its disclosure or omission would likely influence an investor’s decision-making process. Determining materiality often involves a contextual analysis, weighing both quantitative and qualitative factors. For example, a minor discrepancy in financial reporting may be immaterial in isolation but could become significant when viewed as part of a broader pattern of misrepresentation. The examination frequently tests candidates’ grasp of such distinctions, assessing their ability to discern when information crosses the threshold from trivial to consequential.

One of the most challenging topics within the regulation of securities and issuers concerns restricted and controlled securities. These are securities acquired through private offerings or other limited circumstances that impose resale restrictions under federal or state law. Their main exemption for registration is typically found within regulatory rules that allow for resales under specific conditions, such as holding periods or volume limitations. The purpose of these restrictions is to prevent the unregulated distribution of securities to the public without adequate disclosure. Candidates must understand how such exemptions function in practice, recognizing when a resale may occur legally and when it constitutes an unregistered distribution in violation of the law.

Disclosure obligations extend beyond the initial registration phase. Issuers must maintain ongoing transparency through periodic reporting, updating investors on financial performance, management changes, and material events. Failure to make timely or accurate disclosures can result in administrative sanctions, civil liability, or criminal prosecution. The importance of continual disclosure lies in preserving the integrity of the market and enabling investors to make informed decisions based on current data rather than outdated or incomplete information. The examination evaluates candidates’ awareness of these continuing duties and the potential consequences of noncompliance.

In addition to registration and disclosure, the law imposes strict requirements regarding promotional activities associated with securities offerings. Any advertisement, prospectus, or sales literature used in connection with an offering must be filed with the administrator and must not contain any false or misleading statements. The principle of fair representation governs all promotional communication, ensuring that investors receive balanced information reflecting both risks and rewards. Overly optimistic projections, selective presentation of data, or omission of material facts constitute violations of this principle. The ethical dimension of promotion, therefore, intertwines with the legal framework, reinforcing the notion that integrity is inseparable from commerce.

The concept of merit review distinguishes state securities regulation from federal oversight. While the federal system primarily focuses on disclosure, state administrators possess the authority to deny or revoke registration if they determine that a security is inherently unfair, inequitable, or unsuitable for public investment. This discretionary power allows states to act as a final safeguard against exploitative or overly speculative offerings. The exercise of merit review requires judicious balance, as excessive intervention can stifle legitimate capital formation, while laxity can expose investors to undue peril. Candidates must understand the philosophical and practical distinctions between disclosure review and merit review, as this awareness reflects the broader regulatory ethos underpinning the Series 63 examination.

Issuers must also adhere to procedural duties surrounding escrow arrangements and the handling of subscription funds. In certain offerings, particularly those contingent upon achieving a minimum sale threshold, the proceeds from investors must be held in escrow until the conditions of the offering are met. This safeguard prevents premature use of funds and ensures that investors receive either the securities they were promised or a full refund if the offering fails to materialize. Mismanagement or premature release of escrowed funds constitutes a serious violation, exposing both issuers and their agents to disciplinary action.

The state securities administrator’s authority extends beyond registration to enforcement and oversight. Administrators may suspend, revoke, or deny registration upon finding that an issuer has engaged in dishonest or unethical practices, provided false information, or violated securities laws. They may also impose fines or seek injunctions to prevent ongoing violations. The administrator’s investigative powers are broad, allowing examination of books, records, and testimony. Cooperation with regulatory inquiries is not merely advisable but mandatory; refusal to comply can itself be grounds for disciplinary action. The examination tests candidates’ understanding of administrative procedures, emphasizing both substantive knowledge and procedural propriety.

The ethical obligations of issuers extend beyond compliance with written law. They encompass a duty of candor, fairness, and stewardship toward investors and the market as a whole. An issuer that views transparency as a burden rather than a moral imperative erodes the social fabric of finance. Ethical issuers recognize that disclosure is not an adversarial requirement but a mechanism of trust, transforming private enterprise into a public covenant. Candidates must appreciate that while statutes define minimum standards of conduct, true professionalism aspires to a higher ideal—one in which honesty and accountability form the foundation of every transaction.

Conclusion

The role of the securities agent within this context cannot be overstated. Agents act as intermediaries between issuers and investors, translating complex regulatory concepts into accessible information. Their responsibility includes verifying that securities they sell are properly registered or exempt, disclosing all material facts, and refraining from any misrepresentation. Agents must maintain awareness of both state and federal requirements, as the interplay between the two can create nuanced obligations. Failure to verify the legitimacy of an offering can result in both personal and institutional liability, underscoring the agent’s critical role as a guardian of investor protection.

Ultimately, the regulation of securities and issuers constitutes an elaborate architecture designed to balance freedom with responsibility, innovation with caution. It demands that those who raise capital do so in a manner that honors truth, respects investors, and preserves confidence in the financial system. Every statute, exemption, and disclosure rule serves this broader purpose, weaving together legality and morality into a coherent whole. The candidate who comprehends these principles not only prepares for examination success but also internalizes the ethical compass that defines the very spirit of the securities profession.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I get the products after purchase?

All products are available for download immediately from your Member's Area. Once you have made the payment, you will be transferred to Member's Area where you can login and download the products you have purchased to your computer.

How long can I use my product? Will it be valid forever?

Test-King products have a validity of 90 days from the date of purchase. This means that any updates to the products, including but not limited to new questions, or updates and changes by our editing team, will be automatically downloaded on to computer to make sure that you get latest exam prep materials during those 90 days.

Can I renew my product if when it's expired?

Yes, when the 90 days of your product validity are over, you have the option of renewing your expired products with a 30% discount. This can be done in your Member's Area.

Please note that you will not be able to use the product after it has expired if you don't renew it.

How often are the questions updated?

We always try to provide the latest pool of questions, Updates in the questions depend on the changes in actual pool of questions by different vendors. As soon as we know about the change in the exam question pool we try our best to update the products as fast as possible.

How many computers I can download Test-King software on?

You can download the Test-King products on the maximum number of 2 (two) computers or devices. If you need to use the software on more than two machines, you can purchase this option separately. Please email support@test-king.com if you need to use more than 5 (five) computers.

What is a PDF Version?

PDF Version is a pdf document of Questions & Answers product. The document file has standart .pdf format, which can be easily read by any pdf reader application like Adobe Acrobat Reader, Foxit Reader, OpenOffice, Google Docs and many others.

Can I purchase PDF Version without the Testing Engine?

PDF Version cannot be purchased separately. It is only available as an add-on to main Question & Answer Testing Engine product.

What operating systems are supported by your Testing Engine software?

Our testing engine is supported by Windows. Andriod and IOS software is currently under development.